Buick Bugle: How are Chrysler and Buick Connected?

Chrysler's Chrysler was featured in the August 2019 issue of the Buick Bugle. George Holt links Walter P. Chrysler to both automobile companies and my favorite Chrysler.

Enjoy,

Howard Kroplick

Photos courtesy of Richard Lentinello of Hemmings Classic Car

We have all heard of Walter Chrysler, the Buick Corporation, The Great Gatsby, and the US Merchant Marine. How can they possibly be related? Well they are.

Walter Percy Chrysler was born in Wamego, Kansas, the son of Anna Maria and Henry Chrysler. He grew up in Ellis, Kansas where he began his career as a machinist and Chrysler. He grew up in Ellis, Kansas where he began his career as a machinist and railroad mechanic. He took correspondence courses from International Correspondence Schools in Scranton, Pennsylvania earning a mechanical degree from the correspondence program. He then spent a period of years roaming the west, working for various railroads as a roundhouse mechanic with a reputation of being good at valve-setting jobs. He worked his way up through positions such as foreman, superintendent, division master mechanic, and general master mechanic. In 1901, after an engagement of nearly five years, Chrysler married his childhood sweetheart, Della Forker, and they settled in Salt Lake City Utah where Chrysler was working for the Denver and Rio Grande Railway (later part of the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad Company). The couple had four children—Thelma, Bernice, Walter, Jr., and Jack. From 1905–1906, Chrysler worked for the Fort Worth and Denver Railway in Texas and later lived and worked in Oelwein Iowa at the main shops of the Chicago Great Western.

The pinnacle of his railroading career came at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he became works manager of the Allegheny locomotive erecting shops of the American Locomotive Company (Alco).

Chrysler's automotive career began in 1911 when he received a summons to meet with James J. Storrow, a banker (from Boston, Mass.. after whom that city’s Storrow Drive is names-ed.) who was a director of Alco. Storrow asked him if he had given any thought to automobile manufacture. Chrysler had been an auto enthusiast for over five years by then, and was very interested. Storrow arranged a meeting with Charles W. Nash, then president of the Buick Motor Company, who was looking for a smart production chief. Chrysler, who had resigned from many railroading jobs over the years, made his final resignation from railroading to become works manager (in charge of production) at Buick in Flint, Michigan. He found many ways to reduce the costs of production, such as putting an end to finishing automobile undercarriages with the same luxurious quality of finish that the body warranted.

In 1916 William C. Durant, who founded General Motors in 1908, had retaken GM from bankers who had taken over the company. Chrysler, who was closely tied to the bankers, submitted his resignation to Durant, then based in New York City. Durant took the first train to Flint to make an attempt to keep Chrysler at the helm of Buick. Durant made the then unheard-of salary offer of $10,000 a month for three years, with a $500,000 bonus at the end of each year, or $500,000 in stock. Additionally, Chrysler would report directly to Durant, and would have full run of Buick without interference from anyone. Apparently in shock, Chrysler asked Durant to repeat the offer, which he did. Chrysler immediately accepted. Chrysler ran Buick successfully for three more years. Chrysler would completely revolutionize Buick’s manufacturing system, introducing assembly-line processes pioneered by Henry Ford and more than tripling production. Under Chrysler’s leadership, Buick became the strongest unit of General Motors and the most successful automobile brand in the country.

Durant and Chrysler were both men of strong personalities, and they were often in conflict, especially over expenditures. Chrysler was a brilliant cost-cutter who had always maintained that keeping the company lean was the secret to building affordable cars. He was famous for having said, “Whenever there is a hard job to be done, I assign it to a lazy man; he is sure to find an easy [i.e., efficient] way of doing it.” In contrast, Durant was a dreamer who favored the idea that spending more money could lead to greater growth.

In 1919 the two men’s different philosophies came to a head over the cost of frame manufacturing. Chrysler wanted to sign a contract with an outside company to supply Buick with its frames, at an estimated savings of close to $2 million a year. Durant simultaneously announced plans to build a $6 million Buick frame plant in Flint. Chrysler, unable to stomach such a wild expenditure, resigned from the company. Although Durant and Chrysler did not see eye-to-eye on business matters, they remained lifelong friends, and Durant dedicated his unfinished autobiography in part to Chrysler. Durant paid Chrysler $10 million for his GM stock. Chrysler had started at Buick in 1911 for $6,000 a year, and left one of the richest men in America.

Chrysler was then hired to attempt a turnaround by bankers who foresaw the loss of their investment in Willys-Overland Motor Company in Toledo, Ohio. He demanded, and received, a salary of $1 million a year for two years, an astonishing amount at that time. When Chrysler left Willys in 1921 after an unsuccessful attempt to wrestle control from John Willys, he acquired a controlling interest in the ailing Maxwell Motor Company. Chrysler phased out Maxwell and absorbed it into his new firm, the Chrysler Corporation, in Detroit, Michigan, in 1925.

What was Chrysler to do with his wealth? He did two things: he built a Manhattan skyscraper and he bought a mansion. Chrysler was named Time magazine's Man of the Year for 1928, the same year he financed the construction of the Chrysler Building in the heart of midtown New York City, which was completed in 1930. The Chrysler Building at 1,046 ft. was the world’s first supertall building claiming the title of World's Tallest Building for 11 months until the Empire State Building was completed.

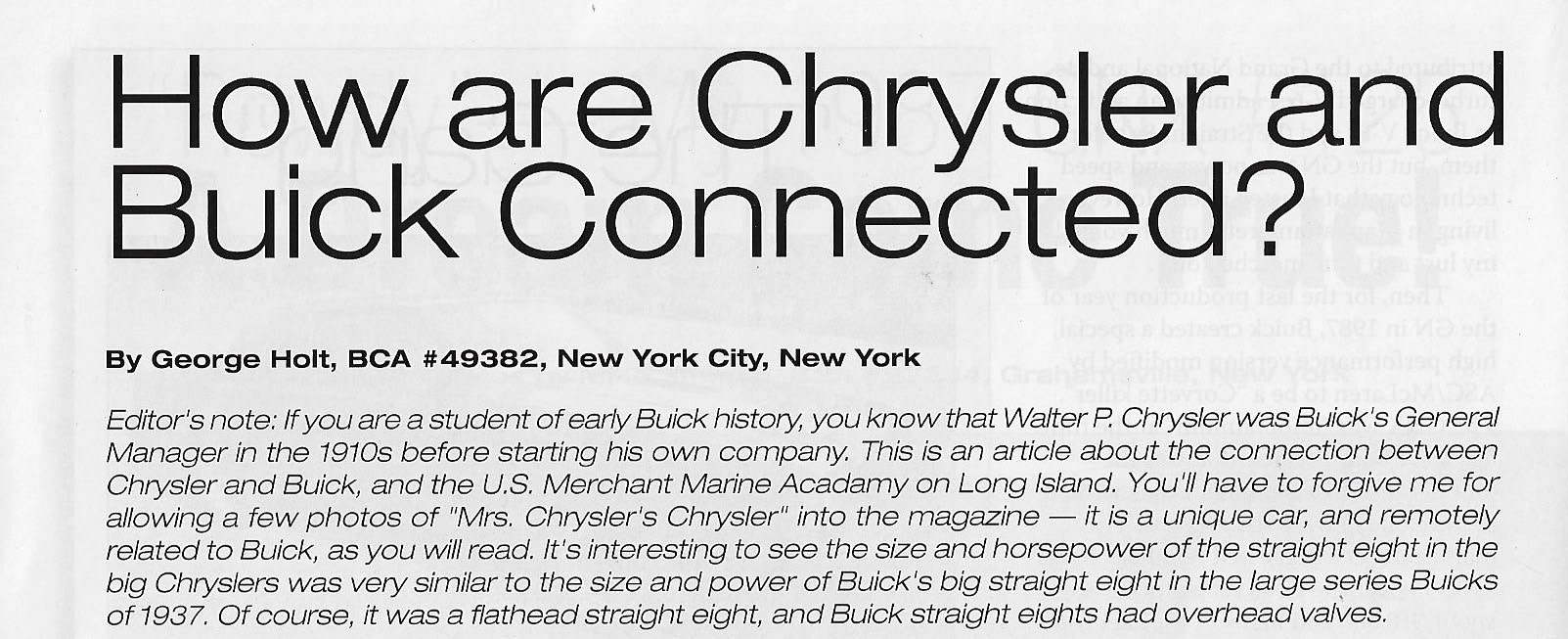

In 1923, for $175,000, Chrysler purchased a twelve-acre waterfront estate at Kings Point on Long Island. The mansion was designed c.1916 by Henry Otis Chapman in the French Renaissance style and built in 1917. The mansion had 23 rooms 10 baths with all the luxury appointments: each bedroom decorated in a different classical style, sunken and formal gardens, outdoor and indoor swimming pools, terraces, paths, and pergolas. It was situated on 450 ft of prime water front frontage with a 150 ft long pier big enough for yachts. From its front windows and terrace you had, and still have, a sweeping magnificent view of western Long Island Sound leading into the East River with the Manhattan skyline in the distance. It is said that the reason Walter Chrysler bought this particular estate was for that view, so he could watch his Chrysler Building rising against the city skyline. Chrysler named it Forker House after his wife’s family name.

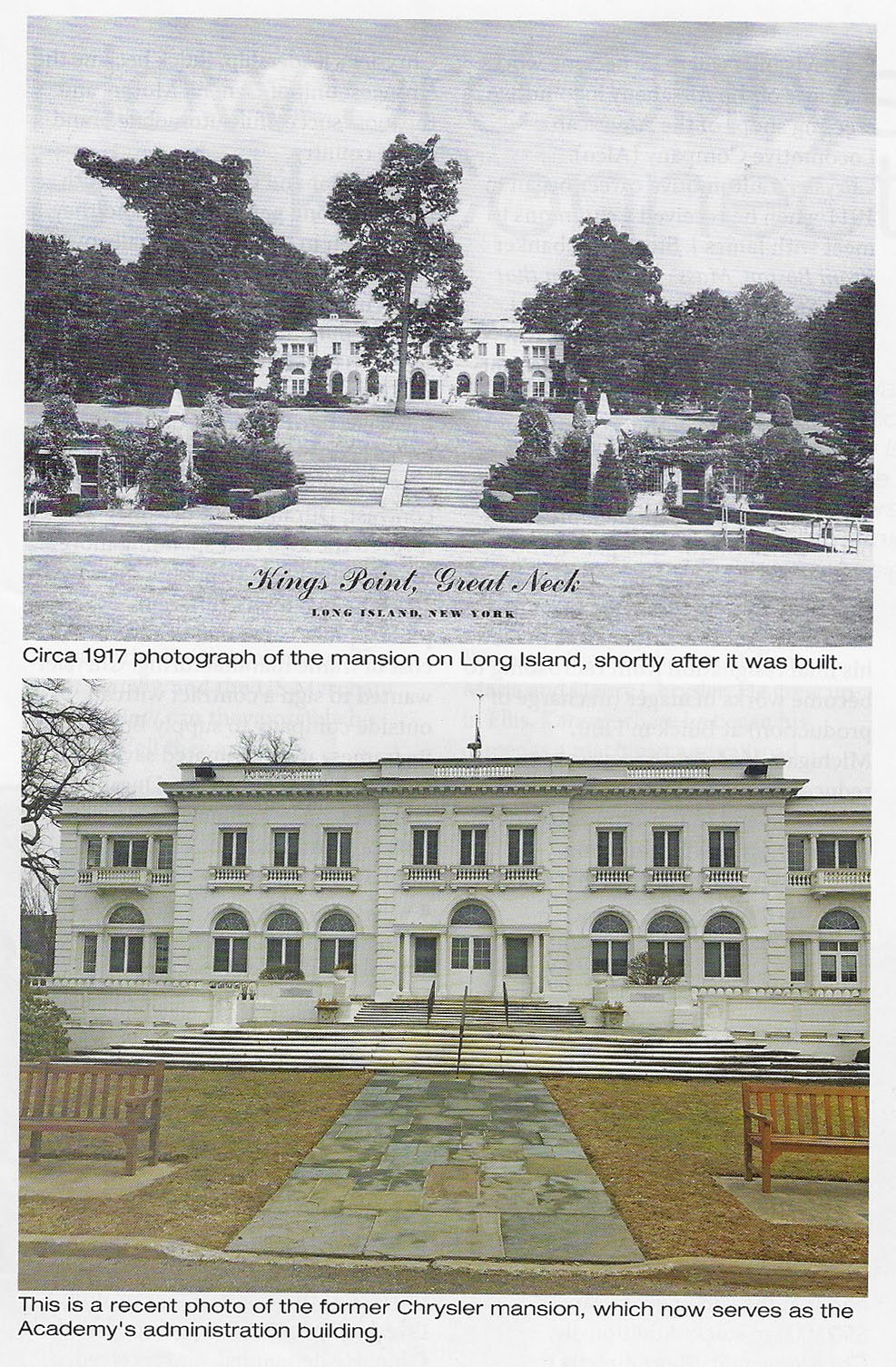

Chrysler turned 61 in the spring of 1936 and decided to step down from an active role in the day-to-day business of his company. Two years later, his beloved wife Della died at the age of 58 and Walter, devastated at the loss of his childhood sweetheart, suffered a stroke. His previously robust health never recovered from this, and he succumbed to a cerebral hemorrhage in August 1940 at his Forker House. The estate was put up for auction in 1941 and was purchased by the War Shipping Administration a year later for $100,000 for the new Merchant Marine Academy.

Origin of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy

A disastrous fire in 1934 aboard the passenger ship SS Morro Castle, in which 134 lives were lost, convinced the U.S. Congress that direct federal involvement in efficient and standardized training for merchant seamen was needed. Congress passed the landmark Merchant Marine Act in 1936, and two years later, the U.S. Merchant Marine Cadet Corps was established. Construction of the academy on the grounds of Walter Chryslers former estate began in 1942. The Merchant Marine academy was dedicated in 1943 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. World War II required the academy to devote all of its resources toward meeting the emergency need for Merchant Marine officers.

As the war drew to a close, plans were made to convert the academy's wartime curriculum to a four-year, college-level program to meet the peacetime requirements of the merchant marine. In 1948, such a course was instituted. It was made a permanent institution by an Act of Congress in 1956. The United States Merchant Marine Academy (also known as USMMA or Kings Point), is now one of the five United States service academies (along with West Point, Annapolis, the Air Force Academy, and the Coast Guard Academy). It is charged with training officers for the United States Merchant Marine, branches of the military, and the transportation industry. Midshipmen (as students at the academy are called) are trained in marine engineering and all facets of subjects important to the task of running a large ship. The academy is administered by the U.S. Maritime Administration, under the United States Department of Transportation. In the early months after the USMMA opened its doors, the rooms of Walter P. Chrysler’s former mansion were used for classes and dormitory space. It now serves as the Academy’s main administration building 'Wiley HalI”.

Mrs. Chrysler's Chrysler

Another of things Walter Chrysler did with his wealth in 1937 was to have a “one-of one” seven-passenger Imperial Model C-15 Town Car limousine custom built by LeBaron as a gift for his wife Della. The car’s dimensions were: 144-in. wheelbase, 19 ft, length, 6-ft. 6-in. width, 5-ft. 10 in. height, and 6,300 lbs. weight. LeBaron built the car to Walter Chrysler’s desires to have something truly special for his wife. Based on a standard 140-inch-wheelbase 1937 Imperial, just about everything from the firewall on back was changed or fabricated from new, including cutting the chassis and adding several inches to the wheelbase. While most of the body was crafted in aluminum, the unique rear fenders were steel. Lengthening the body beyond the end of the frame spars required extensive use of wood to support it. It was painted black, with leather interior panels, and luxurious upholstered seats.

Since it was custom built for a lady, its interior appointments were designed for her comfort. There were lighted mirrors on each side of the commodious rear seat for a lady to adjust her hair. The divider panel between the chauffeur compartment and the passenger featured an elaborate, handmade wooden vanity, fashioned in striking, light-catching “flamed” maple with compartments for perfumes, combs, and makeup. It was powered by a straight 8-cylinder in-line engine, 130 horsepower, 323.5 cubic inches displacement, 3-speed manual transmission with automatic overdrive. It is believed to be the first and only automobile with spring loaded assisted rear windows and door locks. Della Chrysler enjoyed the car only briefly until her death in 1938. After Walter Chryslers’ death in 1940, the LeBaron limousine was inherited by their daughter, Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. It later passed into the hands of Huntington, New York, resident Harry Gilbert, who donated it to the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum in 1959. The museum did not display the car, but left it in a storage garage. There the car remained unused and unseen.

In 2011 Howard Kroplick, local avid car collector and historian, accidentally spotted the neglected car while looking for another. Mr. Kroplick has a small eclectic collection of unusual and very rare cars- a 1948 Tucker, among others. The car had deteriorated significantly due to improper storage over the years, but was 95% intact. When Mr. Kroplick asked about the car, the museum staff told him it wasn’t part of their regular collection and since they were unable to afford its restoration, they were planning to sell it eventually. A private auction sale was arranged. Mr. Kroplick won the auction with his bid of $275,000 which went to an endowment for museum archives and exhibits. When Mr. Kroplick brought the car home in 2012 the odometer read 25,501 miles. Nicknamed “Mrs. Chrysler’s Chrysler”, from 2012 to 2014 the car was restored and made its show debut at the 2014 Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance where it was Awarded First in Class for American Classic Closed. It won Best in Show at Hemmings Concours 2015. It was also featured in an article in the 2015 issue of Hemmings Classic Car where it was pictured in front of Walter Chrysler’s Kings Point mansion, a spot where it was last seen 75 years ago.

Comments

Oh, hey; this reminded me that my father’s (Sam, Jr.‘s) last job, before he became one of of NYC’s leading funeral directors (along with his father, Sam, Sr.), was as a construction supervisor on the Chrysler Building’s foundation. That may have been for Godwin Construction. He was a Chrysler owner almost his entire life. He bought a big Nash (later part of AMC/Chrysler) 8 roadster ca. 1930 after the owner went out a window in the Crash, bought a giant Pierce Arrow roadster as a second car for Mom, who had to take her road test in it on the fierce W. 116th St. hill, drove Dodges to ‘41, tried a ‘49 Chevy as a second car, despised it, then tried a ‘50 2-speed Powerslide, dumped it almost instantly, and stayed with Chryslers ever after. Dad had a brand new Hemi block split and wrote directly to Walter in his fury, even though I assured him WPC was dead by then. Oh, I come by that fixation honestly! It was the new ‘37 or ‘38 Dodge in which he drove me on the LIMP just as soon as he heard it would close down; he did things like that on the spur of the moment and I rode standing up in the back seat hanging on the the braided rug rope for dear life. I even remember that we drove out on No. Blvd., through old Flushing. Bet he ran Dead Man’s Curve at full tilt, too! I love the connections and recollections the blogs drag out of me and the other LIMPers. Thanks, Howard. Sam, III

Sam - that is neat! That was my next question but you answered it - which car was that rolled down the Motor Parkway with you in it? Wish I had the opportunity to do so too but was born too late. Sounds like it was a wild and unforgettable ride! The link below is the closest I can now get to it.

https://youtu.be/XnUZBGSvKWQ

The saying that Walter Chrysler bestowed upon a ‘lazy person’ has much truth to it. Sometimes a hard worker can become very fixated on their task and wear themselves out. Good Leader’s know who to seek out for certain tasks.

We always like to know your recollection’s, Sam III. Your father expressing his disgust to Chrysler is priceless! I hope the company reimbursed him in some way.

Sorry, Frankl Dad was a daredevil driver but not THAT crazy - no crashing through fences or bouncing across fields (it was I that did the latter). Funny, now I clearly remember the Flushing stretch - there was a long row of low Tudor-style stores, with diagonal-pattern roof shingles, right up against the roadway on the south side of No. Blvd., probably out around {?} Murray Hill. Your linking the W. C. Fields movie reminds me that there were other films shot on the LIMP; 1937’s “Topper” comes instantly to mind - the Flying Wombat segment. Uh, oh; that was the custom ‘36 Buick Roadmaster roadster. See the 26 Jul 2011 blog. The Wombat was the Phantom Corsair on a ‘37 Cord 810 chassis and was in 1938’s “The Young at Heart”. Both cars were bodied by Bohman & Schwartz. Well, ONE of those films was supposedly shot on the LIMP. I’d like to post (or see posted) a full list. Sam, III

Howard becomes famouser and famouser as we see in Newsday today.

Congrats on all your successes as the town historian.

Best of luck as you move into the next chapters of your life.